“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times; it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness; it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity; it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness; it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair; we had everything before us, we had nothing before us; we were all going directly to Heaven, we were all going the other way.” So begins “A Tale of Two Cities” by Charles Dickens (released in daily bursts, one hundred and fifty years ago), which could also serve as an apt commentary on the state of education as it stands, if not in America, at least in Los Angeles where I’m privy to its vicissitudes.

Education in Los Angeles is a tale of at least three cities: private school, good public school and not-so-good public school. It is also a tale of one city—a city organized, as perhaps all cities are, by money.

When our first child was approaching the age of school, we set to educate ourselves about what to do—and in a city where the in-the-know parents position themselves from preschool so as to be accepted to the “right” private schools, we were a day late and more than a few dollars short to the picnic.

Our first rude awakening was to learn that the rating for our local school at the time was amongst the very lowest in all of Los Angeles, and so we applied to magnate schools but were told that the odds of getting in were very low. We could neither afford private school nor politically endorse it, so we planned to move to another apartment, willing to pay more to be in a “good” school neighborhood, but alas we could not even afford the lowest rent apartments in the good school areas.

Meanwhile, some friends all but insisted that we apply to a little private school that they loved, and which was very different from many of the others—a sort of progressive “hippy school” by reputation. We did apply and, awkwardly, we got in while our friends did not. But then I had the problem of paying for it… I told the director that I didn’t want to say “no” to something I wanted for my child, but I also didn’t want to say “yes” to something I could not afford. She called me back with a generous offer of financial assistance and thus began my children’s private school education on a roller coaster of ambivalence, blessings and challenges (i.e. the first play date at some kid’s mansion).

Over the years my income went up along with the amounts I could, and do, pay… but still, my accountant’s drum beat of advice remains the same: “put your kids in public school” (i.e. if you ever hope to retire, which I suppose I have resigned myself to foregoing). While Dickens has been criticized (by the likes of George Orwell) for “failing to offer solutions,” I’ll stand with Charles on observing the world as I see it in the hopes that increased awareness and consciousness may lead truly to no child being left behind (i.e. a culture that chooses to value education by paying teachers significantly more money).

While I have sacrificed to ensure my kids’ best chance at an education, I also promised myself that I would try to do what I could to change the state of things regarding the discrepancies and unfairness that simply do not sit well on my heart. I’ve discussed this at length with friends who are politically connected, and have been humbled by the myriad crosscurrents of power and influence that block real change. And yet I intuit that if we were to more widely recognize that our collective malaise may stem, in part, to the unseen (and yet somehow felt) angst of children and families who many of us may never consciously notice.

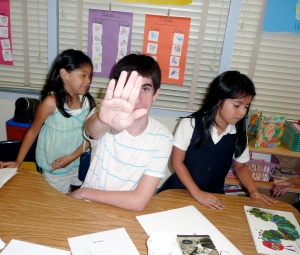

My son volunteered in a classroom this past summer, and he was saddened to learn that the less-advantage school in the far recesses of the San Fernando Valley had seen its arts program cut, that the teacher had to buy supplies out of her own pocket, and that at least one child with clear social and emotional issues ended up being my son’s one-to-one responsibility (in part due to parents who knew nothing about how to advocate and work the system to get the help that is their legal right. See former post about IEPs: http://tiny.cc/EJRpY).

In a recent guest blog in the NY Times, a parent of two, Jody Becker wrote about volunteering, not at her child’s “good” public school (which was overrun with helpful and involved parents and with children doing rather well), but with the tale-of-two-cities “bad” one just a short distance away.

As part of her world-view and motivation to do this she wrote: “For ten years, I spent most of my days in Chicago Public Schools, a public radio reporter looking for ways to amplify the stories of the kids, teachers and educators stuck in mostly sub-standard schools, struggling for help. Stories about determined parents who pushed the schools to teach their kids to read and write, even if those kids had somehow been passed along and were already in 8th grade; stories about principals struggling to re-invent schools in poor, hurting communities that had given up; the even sadder stories of kids whose own poorly educated, desperate and sometimes jealous parents sabotaged their own children’s education.” (for whole post see: http://tiny.cc/IyAt7).

I honor this as exemplary parenting (her volunteering and her raising our collective consciousness by writing about her concern for kids beyond her own)—the very essence of dedicating some of our spirit and actions to all our collective children.

Namaste, Bruce

{ 2 comments… read them below or add one }

Good article on Green Dot. It is one of the charter school operators I support. They take over and operate schools in the toughest neighborhoods in L.A. The city needs more of this.

latimes.com/news/opinion/la-ed-locke28-2009sep28,0,3422791.story

latimes.com

A YEAR AT LOCKE

Cash for the classrooms

Green Dot Public Schools has been able to reduce class sizes by watching the pennies and going after grants and state funding. It raises the question of whether L.A. was shortchanging the students.

September 28, 2009

“Sometimes they don’t see how things are.”

— Handwritten student posting on a bulletin board at Locke High School, explaining why the media don’t always tell the truth about inner-city schools

It requires a second or even a third look at Locke High School to discern the changes this fall, one year after it was taken over by charter operator Green Dot Public Schools. The uniforms are still an ensemble of chinos and polo shirts. The teenagers still gather in the quad for lunch. But almost without exception, the students now wear those uniforms without complaint, unlike last year when they would shrug off the shirts as soon as they thought no one was looking. And instead of huddling on the quad with a few friends in clumps, a large group plays pickup soccer on the grass.

The teachers are still mostly young — well, one tough year older — and passionate about the mission of teaching disadvantaged students. The big difference: There are 43 more of them than last year, a 25% increase. And a tour of classrooms — English, math, chemistry — shows fewer students in each. Average class sizes, which had hovered in the low 30s last year, are now in the mid-20s.

This isn’t just a change from the year before; it stands in marked contrast to the Los Angeles Unified School District and many other public school systems that have laid off teachers and increased class sizes because of miserable education funding. At the same time, Green Dot maintains order on what was a traditionally unruly campus by spending hundreds of thousands of dollars more on security than most schools.

Many charters use private donations to enhance educational offerings, but Green Dot leaders say they use only public funding for the day-to-day operation of their schools. Part of the Green Dot mission from its inception was to show that charters could offer a superior education with the same resources as public schools. And although Locke has a pool of private grants, it is using that money solely to make the five-year transition from an urban high school of 2,600 students to a series of small academies. Green Dot brought on several of the academies’ principals a year before the takeover, for example, to plan the transition. Money is currently being spent on shop equipment for the new school of architecture, construction and engineering — a vocational program that will nonetheless put its students through all the courses required for entrance to four-year colleges.

So it is instructive to study the ways in which Green Dot managed to lower class sizes to levels that would be the envy of many more affluent California public schools. Such an examination reveals the years of neglect and mismanagement by L.A. Unified; it also sheds light on the historically inefficient use of revenue in the district that has kept money out of classrooms.

Green Dot lobbied for, and won, extra state funding for Locke under the 2004 Williams settlement, a landmark case in which California agreed to set aside money for low-performing schools after it was accused of shortchanging disadvantaged students. Locke clearly qualified for a share of this money, and it is unclear why L.A. Unified, which for years ignored the festering problems at the Watts school, never helped it obtain the extra cash. Green Dot also went after and received a grant intended for public schools with large populations of students who are not fluent in English.

But these funds account for only a few of the new teachers at Locke. Most of the rest comes from Green Dot’s relentless squeeze on administrative costs. The charter operator takes 6% of the student funding for central office expenses. The rest goes directly to its schools, which decide how to spend it. It is hard to compare administrative costs from one system to another, but a USC study in 2007 concluded that California charter schools put 75% of their money directly into classrooms, compared with 65% in public schools. Green Dot pays its teachers more than they would earn in public schools, but saves money with scaled-back retirement benefits.

The Green Dot system also breaks down the central bureaucracy and gives principals an incentive to watch their pennies. When a window breaks at a Green Dot school, the principal calls around to local businesses for the best deal. When the same thing happens at an L.A. Unified school, the plant manager for the school calls the district’s central service desk, which enters the information into an “asset work management system” and forwards it to the district’s own window-glazing shop — one of many repair shops operated by the district — where employees who are paid above prevailing wage will fill the order.

Zeus Cubias, an assistant principal at Locke who spent years there before the takeover, said the school’s previous administrators ordered high-end metal and glass desks for their offices. Not held accountable for smart spending under the district, they saw no reason to scrimp on office furniture. No one knows where those desks went, but the current school offices at Locke are far from elegant.

And because Locke’s truancy rates are about 10 percentage points lower than they were under L.A. Unified, the school gets more per-pupil funding, which is tied to average daily attendance. The school’s history is one in which the population of each class fell off sharply each year because of dropouts and community transiency, but already Green Dot is retaining more students.

Perhaps such hopeful signs are reflected in the English class where students are asked to post on the bulletin board their opinions about the media and urban schools. One reads:

“Locke is not a bad school and most of the students have high ability to learn.”

Copyright © 2009, The Los Angeles Times

Thanks for this. I am aware of several excellent charter schools as well, and my hope is that wider dispersal of these ideas represent a more grass roots and community based way of serving all our kids, and not feeling defeated by the problems of huge institutions that might appear to make change impossible. In the end, it’s on us individuals to care if we want a better society as well as happier lives not just for our children but for ourselves.