Boxing Day, a holiday in many countries (but not in the U.S.), is traditionally celebrated on December 26th. The name derives from the tradition of giving gifts to those less wealthy than one’s self, gifts that were stored in a “Christmas Box” and distributed the day after Christmas.

I have also, probably incorrectly, been told by a Brit or two that Boxing Day was the day you boxed up the presents you got, but didn’t want to keep—or was it a day for boxing up ornaments?

For me, the notion of Boxing Day brings to mind one of my father’s more memorable, albeit unfortunate, parenting strategies. Admittedly, my brother and I, a scant and rivalrous eighteen months apart, fought an awful lot when we were children. As a parent I can certainly understand how annoying sibling quarreling can be (although I guess I’m somewhat fortunate that my kids limit their strife to sarcasm and verbal snipes and haven’t fallen to blows in recent memory). My dad seemed to have his own dark view of sibling relationships (he professed to hate his sister and went for years without speaking to her despite the fact that she lived precisely one block away, on the same street).

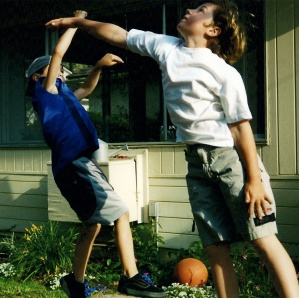

And so it was that my dad came home from work one evening with two pairs of boxing gloves. He explained that if we were going to fight, at least we would learn to fight like gentlemen. Neither my brother nor I were game for this, but after dinner we went on a forced march to the basement where my dad helped lace gloves on my brother and I. Just so you can picture the general feel of featherweight children getting ready to step into the ring, bear in mind that I was about nine and my brother seven.

New toys and sports equipment are always interesting to kids, and so the smell of leather and the curving padded contours of the gloves initially distracted us from the grim bout ahead as we practiced holding up our hands and squeezing our fingers to watch how the gloves responded like swollen mittens.

My dad still held onto his angry frustration as he solemnly explained the rules that seemed to distill down to not hitting below the belt and stopping when he announced a round to be over. He sat down on a vinyl barstool fronting the Formica bar, looked at his gold watch and said, “Go!”

My brother and I looked at each other uncomfortably. We were used to fighting because we were angry—and then we wrestled spontaneously and hard until someone cried, or told on the other or gave up. To fight without anger felt terribly artificial and so we danced around each other with our gloves up, not punching. My dad egged us on until my brother started to take swings at me, which I blocked but did not return.

I hadn’t seen Cool Hand Luke at this time, but I think of it whenever I remember this boxing match—with me, as the older brother, cast in the George Kennedy role and my brother getting to play Paul Newman’s Luke. In other words, as the older brother, if I won I was a ridiculous bully and if I lost I was no better than Fredo in the Godfather—a pathetic weakling.

I hadn’t seen Cool Hand Luke at this time, but I think of it whenever I remember this boxing match—with me, as the older brother, cast in the George Kennedy role and my brother getting to play Paul Newman’s Luke. In other words, as the older brother, if I won I was a ridiculous bully and if I lost I was no better than Fredo in the Godfather—a pathetic weakling.

The round ended and my dad measured the break by his watch, waiting for the relentless second hand to make its sweep. I, in particular, protested the whole exercise, but my dad held firm to his angry frustration—his plan to definitively solve our fighting problem by having us fight, insisting that since we wanted to fight, we were going to fight. It was a bit like Dr. Strangelove without irony. “Go!” he called out once more, looking at his watch and then insisting that I fight. Feeling my anger toward my father well up strongly, the rage became too much for me, but unable to challenge my father in any direct manner, I turned my feelings toward my brother and let him have it—swinging at the side of his head and jabbing his face.

The round ended and my dad measured the break by his watch, waiting for the relentless second hand to make its sweep. I, in particular, protested the whole exercise, but my dad held firm to his angry frustration—his plan to definitively solve our fighting problem by having us fight, insisting that since we wanted to fight, we were going to fight. It was a bit like Dr. Strangelove without irony. “Go!” he called out once more, looking at his watch and then insisting that I fight. Feeling my anger toward my father well up strongly, the rage became too much for me, but unable to challenge my father in any direct manner, I turned my feelings toward my brother and let him have it—swinging at the side of his head and jabbing his face.

I can still envision my kid brother’s hurt and angry face, indignant at being hit, and doubly so at being unable to beat me. It didn’t take very long, once I was game for the fight, for my dad to call the match. My brother and I were as far apart as ever and both of us even farther from my dad as we trudged up the stairs behind my father. I vaguely recall silence and my mom’s unspoken vibe of disapproval. Nowhere in Spock was boxing suggested, but my dad was very concerned about too much affection turning us into sissies; instead he sought to shape us into angry young men for some inscrutable reason.

While none of us “attachment parents” would be likely to help our kids lace up the gloves as a coping strategy for sibling rivalries, it is useful to keep in mind the scars, often unspoken, often unconscious, that generations pass along unless some sort of consciousness, bolstered by compassion, allows us to stop doing whatever doesn’t work. Although we may not allow overt fighting, we modern parent may still struggle mightily to facilitate peace in our homes.

If, as parents, we cannot understand and accept that violence and aggression are the Shadow aspects of our own psyches, we risk stirring up violence in those around us (for more on this see “What does it really mean to be passive aggressive?”: http://tiny.cc/cnZAy). Understanding is the root of love, being understood helps quell the very impulses that lead to destructive acting out.

Whatever Boxing Day is really about, I choose to honor my father on it. I honored my mom on Christmas, but it is equally true that without fathers, none of us would be here. My dad is a difficult man, but I know that under all the stubborn oppositionality he loves. I almost always won my fights with my little brother, and in this way I always lost; the worst fight I ever lost, paradoxically liberated me from both fear and from fighting (for that see http://tiny.cc/MKSau). Fathers are both human males but The Father is also an archetype—one that typically contains the fighter and the warrior. My dad seemed to fight the world, and the world has him on the ropes—all the money has slipped through his fingers, and his fight now is to regain his ability to walk… perhaps one day to walk out of the nursing home. He believes he can do it and I root for him. In his softened state my father shows a fighting spirit that is finally not against anything or anyone.

So, on this Boxing Day, let’s dedicate our consciousness to “giving” non-violence, both in actions (including words) and also in our thoughts. Many of us have issues with our fathers, but it serves us, and all our collective children, to relinquish judgment and step up to represent the best aspects of the Father archetype, no matter whether we are male or female, no matter whether father stayed, left, hurt us or helped us. Collectively we all carry many wounds, but we also carry much love and the strength to heal and give what we did not get. Let’s do this with loving kindness for each other, in honor of all our collective children, many of whom are especially at-risk of acting out and getting in trouble because of their own mal-fathered, misunderstood and uncontained anger and frustration.

Namaste, Bruce