While doing for others is a defining characteristic of the hero, it is a quality expected of parents. The essence of leadership is service, but if our children are failing to follow, we must ask ourselves if we are failing to lead. Every era has its particular sort of hero, such as prophet, king or revolutionary—those who stand for what is prized, or needed, in a given epoch. It is my conviction that the biggest need we have, in our families and in our larger world, is for a more compassionate understanding of how we all share this planet and need to take better care of it and each other—starting with our children. The heroes who are fit to lead, inspire and encourage our world are those women and men who are ready, willing and able to take loving care of it—in short, to parent it.

While doing for others is a defining characteristic of the hero, it is a quality expected of parents. The essence of leadership is service, but if our children are failing to follow, we must ask ourselves if we are failing to lead. Every era has its particular sort of hero, such as prophet, king or revolutionary—those who stand for what is prized, or needed, in a given epoch. It is my conviction that the biggest need we have, in our families and in our larger world, is for a more compassionate understanding of how we all share this planet and need to take better care of it and each other—starting with our children. The heroes who are fit to lead, inspire and encourage our world are those women and men who are ready, willing and able to take loving care of it—in short, to parent it.

Parents have always loved their children, but at no time in history have we had such a child-focused culture of specialists, books, activities and expectations of, and for, our kids—not to mention so many parenting books. The collective hunger for support in parenting reflects a zeitgeist of insecurity, perhaps born of the of the paternalistic “science” that rose to dominance in the middle of the last century, and which divided many a parent from her instincts (i.e. suggesting that formula from a bottle was superior to breast milk). While these ideas may now seem misguided and out of fashion, the insecurity they bred ripples to the present day; we may have traded in the flavor of our parenting gurus and experts, but not quite gotten back to actually trusting our own instincts. While I like, espouse and may embody many of these new ideas as a “parenting-expert” in my own right, my central point is that they are only guidelines; when they are blindly embraced by insecure parents as unbending doctrine, they are no longer natural nor holistic in practice. The call to the hero’s journey as a parent is all about leaving the wide, and at times crunchy, trail and heading into the forest of our own true path with our own children—learning to trust ourselves through stepping up to do the unsung hard work of being there for our kids and by learning, via our own trials and errors, what works for us and our children. Passionately doing this is heroic. On the other hand, times, and cultures, do actually change and our massive collective wish to be our best Selves as parents also reflects an ascending ethic of healing, nurturing and appreciating our children and the world we will leave them—a newly emerging, caregiving-as-heroic, zeitgeist. While we must each find a way to make parenting our own, by doing this as our best Selves we meet again in the collective town square to discover that we have made a better world for ourselves and our children.

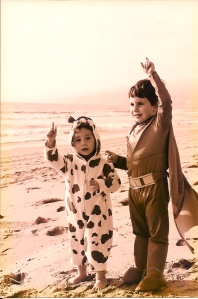

Parenting is a role, but it is also an attitude. We bring the spirit of the parent as hero to life in the way we interact with our children. The parent-hero may be the actual parent of a child, but she may also be a teacher, a nanny, a grandparent—anyone who steps up to get involved in child-rearing, educating, guiding and nurturing. This quiet sort of hero relates to and tends the world rather than conquering, exploiting or controlling it. I see these caregiver heroes showing up all around us—on field trips, at baseball and soccer games, at yoga class. I hear her compassionate heroism in the loving way she talks about everyone’s children at carpool, and in the way one man roots for the other man’s daughter as well as his own. It serves us parents to rethink our beliefs about what constitutes the hero. This may help us deepen our respect for, and improve our relationships with, the nannies, coaches, teachers and other helpers with whom our children interact.

Namaste, Bruce