On my recent summer holiday we visited my sister-in-law and brother-in-law in a small town in Northern California. We love going up there where you sit on the porch and read, swim at the river and walk down to the candy shop after dinner, my kids have grown up going there and it’s home away from home—a place where the theme from the “Andy Griffith Show” plays quietly in the back of my brain.

Just a couple of houses up Main Street from my sister-in-laws old Victorian house is a curious rock. It is a sizable boulder in a hillside with a house’s front porch built right up to it. On the rock is a metal plate explaining how the Indians considered this a “medicine rock” and had carved out hollows on the top where they would sunbathe as part of healing. The plaque mostly celebrates the spot as part of the pioneer experience and the trail that opened up once gold was found in those there hills.

Just a couple of houses up Main Street from my sister-in-laws old Victorian house is a curious rock. It is a sizable boulder in a hillside with a house’s front porch built right up to it. On the rock is a metal plate explaining how the Indians considered this a “medicine rock” and had carved out hollows on the top where they would sunbathe as part of healing. The plaque mostly celebrates the spot as part of the pioneer experience and the trail that opened up once gold was found in those there hills.

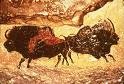

I had also been reading about ancient cave art, and learning how the paintings were not just randomly placed on the cave walls but often followed and made use of natural contours, one looking like a bison’s back situated vertically, another like a horse falling in space. With eyes primed by this reading, I could swear I noticed the natural outline of a bison formed in the wear and weathering of the granite of the Medicine Rock. While this was not a land that had previously contained bison, the verdict on cave art included the notion that our remote ancestors were up to shamanic rite and ritual, and that they were “not painting their diet” (David Lewis-Williams, “The Mind in the Cave: Consciousness and the Origins of Art). It seems quite possible that the native tribes would have known of bison, and quite possibly revered them, much as their even more ancient ancestors had in the caves of Spain and France. In the image below to the left I see the head of a bison; compare it to the image below right of bison on the walls of a cave at Lascaux, France—painted tens of thousands of years ago. Given that the cave painters started with the rock and then elucidated the animal, or its spirit from it, I wondered if the chance resemblance to a bison in the Medicine Rock could have been why it was chosen and honored as having healing powers.

With this in mind, coupled with the powerful spirit energy that I felt around this rock, I searched on line and found only one mention of it, and that just to say it was there (with no explanation of any further history, meaning or purpose).

With this in mind, coupled with the powerful spirit energy that I felt around this rock, I searched on line and found only one mention of it, and that just to say it was there (with no explanation of any further history, meaning or purpose).

In the local book store and asked about books on the indigenous Native American culture and found several shelves of books about the gold rush and history of the region since the white folks arrived, but only one thin “book” about the Northern Maidu tribe—the original inhabitants. It was more like a pamphlet by Marie Potts, with half the pages stapled out of order; yet the writer was a Maidu who knew the lore of her tribe, but there was nothing about the mysterious Medicine Rock. I realized that it was either not such a big deal, or it was and no one who knew anything about it was likely to tell what they knew.

I learned a lot about the Maidu, however, who lived in great harmony with nature and had a completely different notion about “owning” things such as land. Marie Potts’ explanation of their religion told about “Kadyapam,” the Creator who they worshiped by greeting the sunrise with a prayer of thankfulness, then they stopped for meditation at noon and they gave thanks and blessings at sunset. They gave thanks when they made a kill or caught a fish, and it struck me that there are probably more similarities than differences with the core of any system of faith in something higher than one’s own ego self.

Marie Potts also shared their trickster legend of the coyote who was always arguing with the Creator, insisting that there should be sadness, crying and death… and multiple languages so that people won’t understand each other. Coyote won the argument, and hence life has ugliness, but was banished to be a scavenger. And yet it struck me that the artist is also a “scavenger,” a “bricoleur” who chooses treasures from the trash, images from the collective warehouse and words from the dustbin of confusion.

Marie Potts ends her book with reminiscence of being a girl in the cedar bark house of her grandparents and hearing coyotes bark and the hoot of owls in the trees and… “just as it grew light as the sun rose, there came the enchantment of the bird chorus, the orchestra of the Great Spirit all around us. That clean pine smell on the morning wind—Where can we find it now?”

This was in 1975, when Marie Potts was eighty years old. Perhaps today we can try to listen even more closely for the “bird chorus” and look with ancient eyes at the sun light falling today on the coyotes who still find their trickster way to live in Northern California and in modern Los Angeles—in the places Native Americans lived for thousands of years before we got here with our hospitals and schools and mini malls, maybe accidentally wiping away, or at least obscuring, spirit, wisdom and healing.

And if you catch a glimpse of magic in the Medicine Rock or in the shimmering leaves, send a thought, or song, or sigh of gratitude in honor of all our collective children. The younger they are, the better able they might be to explain the Medicine Rock and its secrets to us.

Namaste, Bruce

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

Hi Bruce et al,

I think that whenever our children(and sometimes ourselves)pick up a rock they

feel a part of the earth and sense the beauty and the mystery of it. . Into the pocket it goes. It is a treasure.

Here is to more rock gathering, and the spirit within us.

krk