I’m astride my bike near the big park. G.D., the local bully/cool kid, calls out to me. I turn and look and our eyes meet. With cold inscrutable contempt he takes the rather hard “softball” he is holding and simply beans me in the face with it. He watches my anguished pain, humiliation and shock the way an infant watches milk tossed off the highchair tray, studying his universe of cause and effect, of pleasure and pain.

I’m astride my bike near the big park. G.D., the local bully/cool kid, calls out to me. I turn and look and our eyes meet. With cold inscrutable contempt he takes the rather hard “softball” he is holding and simply beans me in the face with it. He watches my anguished pain, humiliation and shock the way an infant watches milk tossed off the highchair tray, studying his universe of cause and effect, of pleasure and pain.

Time stands still. With a whooshing of surreal clarity everything telescopes back into sharp close-up focus. G.D. is almost unbelievably handsome, charismatic with intermittently smiling eyes and a star aura. He shouts at me to go get the ball—the ball rolling off down the street after it bounced off my face.

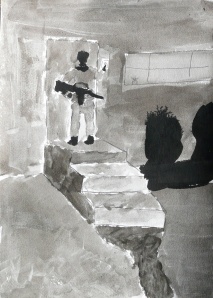

In a millisecond of calculation I picture retrieving the ball and having it thrown in my face again, the lesser toughs cackling like hyenas as my puddle of already liquefied self-esteem seeps into the nearest sewer. Like a refugee running from armed soldiers I make a break for it, blur-pedaling my green Schwinn stingray fastback with equal parts rage and fear, laughter receding behind me.

Panting I race into my house, into the desolate air conditioning, the humming of the fridge, the cicadas screaming outside… outside where I am now afraid to tread. For years I would dread even passing G.D. in the hallway, not realizing that I was but the faintest blip on his radar; never realizing that I was just one of the many weak meaningless kids in the throng, the entire pyramid of those lesser beings than himself.

I could not fathom that he was the youngest of eight or nine kids, mostly boys, or that his parents were reputed to be brutal and his brothers worse, beating him all along the way. I could not possibly have the empathy to imagine that in my soft and trusting face he might have seen, and hated, a loved child—a perfect screen against which to hurl the softball of his mysterious wound.

I hated G.D. with all my heart, and yet found him fascinating and somewhat magnetic. In a town where the barber called everyone, “Hey handsome,” I was neither gay enough nor mature enough to realize that G.D. actually was. When I started to watch Friday Night Lights I realized that Tim Riggins (Taylor Kitsch) was practically a ringer for the G.D. of my childhood. How could a character like that have related to a nerdy sheltered kid with hardly any sense of bad boy or real abuse in him? And yet the irony was that in my own secret self, I was much more a bad boy than G.D. could have imagined. I even think he might have seen me as just one of the kids in the neighborhood; who knows he might even not have completely hated me.

I hated G.D. with all my heart, and yet found him fascinating and somewhat magnetic. In a town where the barber called everyone, “Hey handsome,” I was neither gay enough nor mature enough to realize that G.D. actually was. When I started to watch Friday Night Lights I realized that Tim Riggins (Taylor Kitsch) was practically a ringer for the G.D. of my childhood. How could a character like that have related to a nerdy sheltered kid with hardly any sense of bad boy or real abuse in him? And yet the irony was that in my own secret self, I was much more a bad boy than G.D. could have imagined. I even think he might have seen me as just one of the kids in the neighborhood; who knows he might even not have completely hated me.

I stayed clear through elementary and middle school, knowing which way to avoid walking, when to turn and take another street or skip the park.

My last interaction with G.D. was when, in high school, he and a particularly mean girl both spat water on my back from the drinking fountain when all I wanted to do was get invisibly on the bus and go home to hide in my room.

I was in my sophomore year of college at Michigan when I got a call from a friend at Princeton telling me that G.D. had died in a car accident. G.D. hadn’t gone to college—apparently he’d become a drug dealer and a pimp (but who knew the legend from the truth); the story was that he was driving to Florida to do a drug deal when a car flew off an overpass above him and smashed down on him from above, killing him instantly.

I was a callow nineteen-year-old with a strange and sudden sense of pleasure. Perhaps there was a god, a god that dropped cars on mean people? Perhaps there was something to this karma thing? After all, I now had friends, and a girlfriend and enthusiasm for film and books and music and I was alive and G.D. was dead. I was happy. And I was not guilty about it.

But as the years passed; as I moved from film to psychology; as I worked with troubled kids, with various versions of G.D. by the caseload; as I learned the sad stories of abandonment and abuse that built up to violence and cruelty, I began to re-think G.D. I began to regret feeling happy at his death. His memory haunted me, his face, his eyes that looked more kind and beautiful and wounded as they faded into memory… as he became just a confused, angry, lovely eleven or twelve year old with a softball and a chip on his shoulder, not Dillinger, or Clyde Barrow, or a drug lord or a gangsta, or a thug… just a boy being mean to another boy, I found myself feeling strangely connected with him.

And slowly a warm spot in my heart grew and grew for G.D. and now not a day goes by that I don’t think of him; he’s sort of like a friend now, as much a wise figure as an eternal puer of a misunderstood bad boy now that he’s dead and not all messed up in the way we the living see things, somehow just a sweet boy to be mentored and appreciated, perhaps a Buddha from whom I can learn impermanence and equanimity.

And slowly a warm spot in my heart grew and grew for G.D. and now not a day goes by that I don’t think of him; he’s sort of like a friend now, as much a wise figure as an eternal puer of a misunderstood bad boy now that he’s dead and not all messed up in the way we the living see things, somehow just a sweet boy to be mentored and appreciated, perhaps a Buddha from whom I can learn impermanence and equanimity.

So, this being Bully Awareness Month, perhaps we might think for ourselves about bullies and what they mean to us personally. After all, most readers of this blog are likely to think that bullies are bad (i.e. other people’s kids) and that we must be aware about them in order to protect victims (i.e. our “good” kids). Yes, there is truth that cruelty has consequences, including far too many suicides; however, we may be less likely to notice how our own attitudes could lead to bullying in our own kids.

I was no angel as a child, and there were times I was terribly cruel to other children (and I too was anxious, insecure, angry and confused in a world that seemed cruel and false to me). I have noticed that a lot of bullying seems to come from some sort of anxiety—the need to give away unwanted feelings of rage, fear, inadequacy, shame, etc.—the wish to give them away like a softball to the face of someone, anyone, else.

How might the competitiveness of parents (who often assert, and even truly believe, that they are not being competitive as they push their children into countless activities, honors and AP classes, tutors, resume building and future strategizing) trickle down to kids who simply feel like they are not up to their parent’s standards? Turning to the group for identity and approval, the group itself becomes a roiling game of hot potato where bad feelings end up piling upon the sensitive, the late blooming and the socially different kids.

Could it be that the group is cruel because we parents are, deep down, insecure and thus catty, cutting, devaluing, judgmental and cruel when stressed? Could bully awareness really mean, or at least begin with, awareness of the bully within ourselves? Could the kids we care for somehow mysteriously benefit if we were to recognize the bully in the mirror; the superior attitude, arrogance, condescension and the like that may be so subtle in “successful” people as to be almost completely unconscious (as we think of ourselves as generous, green, politically correct and the like).

I try to be nice, patient and compassionate—and certainly I try to present that aspect of myself in a parenting blog. But I freely admit that I’m not that nice (and don’t expect myself to be); rather I think honesty about the range of our human experience might let us find more authentic connection, and ultimately more safety in the group—more understanding of difference, of strong feelings even when negative, of inclusion and a pro-social ethic in which it is cool to be kind, and where there is room for everyone in the group.

Awareness is very useful—it diminishes the press to “act out.” Thus awareness of our wounds, our angers, our cruelties, our insecurities and the like may allow us to find more equanimity in our hearts and our behaviors. Denial leads to trouble while true awareness leads organically toward compassion. Tolerance for strong feelings allows us to truly hear, and emotionally hold, our children. Shored up by all of us collective parents, even the at-risk kids might be better expressed and less compelled to cruelty.

If there is even the slightest correlation between grown-up anxiety and childhood bullying (be it victim or bully, it is equanimity and the integration of opposites that bring harmony within and without) then it might well be an act of love to deal with the bad feelings within ourselves. And while there may be gold in the poop, bad feelings tend to roll downhill. For this reason we must be like Sisyphus of the crap boulder, ever pushing the dread and inadequacy up hill, finding joy in the arduous process of human life, while protecting our children from our own wounds and insecurities (perhaps just by being more honest and less ambitious for, and through, our children—be it ambition for achievement, toughness, beauty, coolness or any other notion that isn’t in line with our children’s true Selves).

If there is even the slightest correlation between grown-up anxiety and childhood bullying (be it victim or bully, it is equanimity and the integration of opposites that bring harmony within and without) then it might well be an act of love to deal with the bad feelings within ourselves. And while there may be gold in the poop, bad feelings tend to roll downhill. For this reason we must be like Sisyphus of the crap boulder, ever pushing the dread and inadequacy up hill, finding joy in the arduous process of human life, while protecting our children from our own wounds and insecurities (perhaps just by being more honest and less ambitious for, and through, our children—be it ambition for achievement, toughness, beauty, coolness or any other notion that isn’t in line with our children’s true Selves).

So, here’s to brave awareness of, and gallant grappling with, the bully within—our own Shadow selves—in the service of all our collective children.

Namaste, Bruce (and, perhaps even, G.D.)

{ 15 comments… read them below or add one }

Wow. A beautiful story wrought with anguish…and the ever-freeing forgiveness. Just lovely. Thank you.

Hey Denise, thanks for saying so. Namaste

Thank you.

And right back at ‘cha.

“Could the kids we care for somehow mysteriously benefit if we were to recognize the bully in the mirror; the superior attitude, arrogance, condescension and the like that may be so subtle in “successful” people as to be almost completely unconscious?”

Ouch. Guilty as charged, I fear.

While I doubt that my boys will become violent bullies, I worry that they might have a fighting chance of inheriting some holier-than-thou-ness from their parents.

Thanks for the lyrical reminder of how to nurture all of our children by nurturing our own and by getting to know ourselves.

Right with you here, Kristen (one rookie to another)

Shadow and Light. I feel myself becoming most whole when I acknowlege freely both. Yes there is a bully in me. And a bitch and a whiner and a victim. You have opened another door to compassion when you suggest that the way to Love is not denial but a door of welcome.

Thank you.

And, I’m sorry about the softball to the eye, but not too sorry if ya know what I mean. Cuz I think G.D. helped to bring you to this place. We like you here.

Very kind, thanks. Namaste

I think today’s parenting is all about self esteem, self importance and raising our kids to think they are the best. It really is a shame. Because I don’t think kids have changed over the years but the parenting styles sure have. I think if our grandparents could hear all this psychobabble about child rearing they would laugh. It used to be teach your child to respect, be responsible and have reverence. What do kids learn about these things today? I think Mom and Dad do too much and worry too much. Just my opinion.

I think it is facinating how you remember your bully. I guess we all have a bully we remember but the evolution your bully has had in your mind is proof that we can rise above it. See them through a different lens and find the humanity.

Yes, our grandparents would probably laugh as well as cry—as our levels of self-involved narcissism probably go beyond anything they could have envisioned. In the end it may be our cultural emptiness and, finally, disgust with a lack of actually well-being to be born out of all this achieving and competing that finally bullies us grown-ups into more authentic compassion.

Knowing that we are “not really that nice”–and admitting it to ourselves–is perhaps the first step toward bringing more love and kindness into the world. We feel compelled to practice until we start to “get it,” just the way I keep telling myself that, if I keep practicing, someday I will finally manage to do an effortless wheel pose in yoga class. What you practice here, Bruce — honesty, compassion, deep reflection, shining light into dark places — benefits us all. I think you and your readers might like a new blog I’ve been reading, Walking on My Hands. Check it out here:

http://walkingonmyhands.com/2010/10/15/outing-my-inner-fraud/

Hi Katrina, I really liked “Walking on My Hand,” so thanks for the hands-up and for your kind words.

“The Sisyphus of the Crap Boulder?” I know this piece was meant to make us think, and you did your job, but I am giggling like a loon over here. That is awesome!

And good for you for your compassion toward your bully. I do wish God dropped cars on mean people. I’m obviously not very evolved.

Well, I’m not evolved either, I shouted, “Hurrah!” in my head when I heard the car had squished G.D. And though you have come to terms with his treatment of you, I’ll bet a dollar to a doughnut hundreds of others have not, dozens were treated far worse. Many were possibly wrecked for life.

Sometimes, Karma works.

It’s good to hear you grew into a ‘rubber ball’, that his dings and cruelty didn’t dent you, that you’ve made peace and moved on. That’s reassuring.

I hope, one day, I’ll be able to do the same with the memories of my tormentors. Understand, that day has not yet arrived. However, after reading this, I’m going to work harder on getting beyond my past, coming to terms with all that happened. It’s a process, so, one small step at a time. If for nothing else, my relationships and my children will benefit. That’s good enough for me.

Sounds good to me—and if you buy into karma, then the key is to trust that your former torment was your karma and NOT any referendum on your worth or adequacy. Thus accepting the karma past, frees you to break the chains of your past tormentors (OUR past tormentors, it more like it, as we all have them to some extent, and we all WERE also tormentors as well, if you’re going with the karma notion)—this really means working through karma so that any hindering scripts can drop away (such as we are victims, or we are doomed to fail at things).

Once free of the old baggage, as Mary Poppins would have us believe, “anything can happen if you let it.”

Thus, forgive if you can, and if you can’t then trust it’s your karma to hold onto the resentment for a little while longer. We all meet again in the end, and without our masks. Namaste

{ 1 trackback }